Two years of COVID-19: What's next for the pandemic?

Published: 15 March 2022

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a pandemic, two years ago this month, it was clear that the new coronavirus represented a historic threat to global health and that its impact would be felt for years to come.

Since then, the world has adjusted dramatically to the challenge. Countries plunged in and out of lockdown, mask-wearing and self-testing became regular parts of daily life, and members of the public grew used to checking daily infection numbers.

In the worst months of 2020, many people looked forward to a time where COVID-19 no longer dominates our lives. Now, thanks to high levels of immunity built up through vaccination and previous waves of infection, the UK appears to be entering this phase.

Experts from Imperial College London have played a key role during the pandemic in improving our understanding of the virus, with world-leading epidemic modelling and major trials of treatments and vaccine technology.

We spoke to some of our researchers on the pandemic about what the future of COVID might look like in the UK.

Where are we now?

For the first year of the pandemic, it was accepted that strict social restrictions were needed to prevent a devastating peak of hospitalisations from the virus. That changed in 2021, when waves of infection brought on by the Delta and Omicron variants peaked and subsided without major measures being introduced, as mass vaccination helped to reduce transmission and the severity of COVID-19.

All legal COVID restrictions have now been lifted in England and Northern Ireland, and only a few remain in Scotland and Wales. In recent weeks, reported cases across the UK have fallen significantly from a peak of 275,000 infections in one day in early January to around 35,000 cases at the end of February - although daily infections have begun to rise again in recent days.

That experience, along with improvements in treating the disease, has led to speculation that the worst of the pandemic is behind us – a view that was broadly shared with the Imperial experts we spoke to, with a key caveat that a new variant could drastically change the situation.

Professor Samir Bhatt, who worked in Imperial’s COVID-19 Response Team as part of the School of Public Health, explained that the pandemic appeared to be entering “a period of quietness” for high-income countries that have high levels of immunity from vaccination.

“The combination of vaccines, natural immunity, drugs and treatments have basically brought the infection fatality rate, which was extremely high for older people, to a much lower level - to the point where it is higher than seasonal influenza, but not a huge amount higher,” he said.

However, the situation in the rest of the world could be very different over the next year, with countries with low levels of vaccination still likely to see big epidemic waves from the virus.

“In the UK, I think we are entering a more stable phase of the epidemic, because of very high protection levels from vaccination and infection,” said Dr Anne Cori, from Imperial’s MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, who also worked in the COVID-19 Response Team.

“We're less likely to have very big waves of hospitalisations and deaths than we've experienced in the past - but variants can change that.”

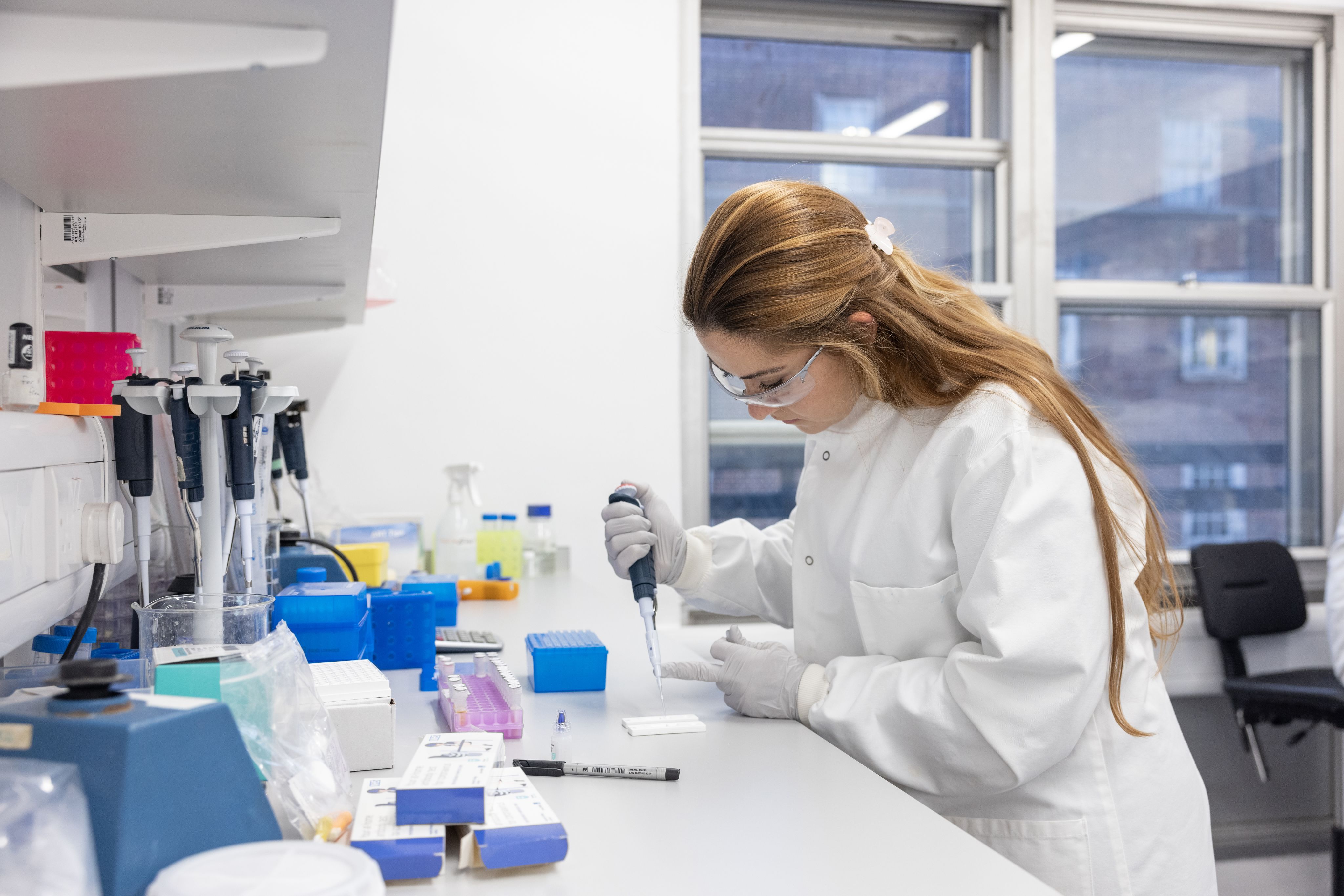

Imperial led the REACT testing programme to track the progress of COVID-19 infections across England.

Imperial led the REACT testing programme to track the progress of COVID-19 infections across England.

Imperial led the REACT testing programme to track the progress of COVID-19 infections across England.

Imperial led the REACT testing programme to track the progress of COVID-19 infections across England.

What comes after Omicron?

While the Omicron variant has led to less severe disease, some scientists are concerned that there is no guarantee that the next variant will do the same.

“We are at a stage where we do not quite understand why some variants are mild or more severe than others and we do not know that entire breadth of opportunity for this virus,” Professor Wendy Barclay, Head of Imperial’s Department of Infectious Disease, said.

“I think it is dangerous to assume that it is inevitable that the next variant will be like Omicron.

“There may be a variant that solves the problem of how to transmit in an immune population in quite a different way to how Omicron has done. You may end up with a quite severe variant, which breaks through the vaccine more and causes severe disease when it does so.”

However, there are hopes that some treatments for the virus will still be able to help patients even if a new variant manages to evade the protection from vaccines.

Professor Anthony Gordon, from Imperial’s Department of Surgery & Cancer, is the UK Chief Investigator for the REMAP-CAP platform trial, which has been evaluating treatments for COVID-19 in hospitals.

He explained that the treatments fall into two main camps: anti-inflammatories and antivirals. "There are those that tackle things like inflammation, the body's response to the virus," Professor Gordon said.

"If you have excessive inflammation, it doesn't matter what has caused it, the anti-inflammatories are likely to work."

“I think it is dangerous to assume that it is inevitable that the next variant will be like Omicron.

For antivirals that target the virus’s ability to infect and replicate in cells, Professor Gordon believes it will depend on whether the variant has mutated in a way that changes the key part of the virus that is targeted – different treatments may end up working better against different variants.

He added that this uncertainty around the virus's ability to mutate and change reinforces why it is important to have ongoing research into patient care for COVID, so clinicians can alter treatments as the circumstances change.

No time for complacency

Despite a more positive outlook for the UK’s epidemic, many of the scientists we spoke to were still worried about complacency around case numbers, as COVID-19 is still infecting tens of thousands of people a day and putting thousands in hospital every week.

From an immunological perspective, Professor Danny Altmann, from Imperial’s Department of Immunology and Inflammation, said he saw a real risk of the virus eroding the gains made in recent decades on what people can expect to receive in terms of healthcare and quality of life.

“The planet missed the boat in early January 2020 for any elimination or eradication [of COVID] because we didn’t have the kind of vigilance we needed to stop it spreading around the globe. It’s too late for that now,” Professor Altmann said.

“But I think there are still opportunities for countries to make different choices. How COVID tolerant they decide to be in the coming years will have an enormous impact on their economies and employment sector and a million other things.”

We have become rather accustomed to hearing large numbers and thinking, well, it could be worse. But it could be a lot better.

That is a view that was echoed by Professor Peter Openshaw, from Imperial’s National Heart & Lung Institute, who warned that the number of people in hospital with COVID was still “unacceptably high”.

“I think we have become rather accustomed to hearing large numbers and, in a way, we are thinking, well, it could be worse. But it could be a lot better,” he said.

While some commentators have sought to argue that many patients in hospital now with COVID merely have the virus rather than it being the main cause of their illness, Professor Openshaw was keen to stress that this was not an accurate way to think about the issue.

"It is clear to my mind that with many of the people who are in hospital for other reasons, but have COVID, that COVID is a contributing factor to making their other condition unstable,” he said.

“For example, people with diabetes, or dementia, or chronic bronchitis, if they catch COVID, they are going to be destabilised – so although the cause of hospital admission may be down as diabetes, the reason they are in hospital with diabetes is because they have COVID.”

However, despite these concerns, Professor Openshaw noted that there was “light at the end of the tunnel” for the pandemic, with Omicron’s milder severity pointing towards a less dangerous disease.

“Clearly patients are much better off now being infected with Omicron than they were with some of the previous variants that had very high hospitalisations and high mortality,” he added.

“It is moving in the right direction, but to my mind, there is a way to go. We must not make light of it.”

The issue of long COVID

The focus of policymakers and health officials over the past two years has understandably been on the immediate impact of the virus in terms of hospitalisations and deaths.

The general understanding in the first months of the pandemic was that most people who got COVID-19 would recover quickly, a proportion of people would be hospitalised and a proportion of those people would sadly die from the virus. However, the reality turned out to be much more complicated than that.

According to an Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey published in January, about 1.3 million people have “long COVID” - a broad term that describes symptoms that last for more than four weeks after an initial infection, such as fatigue, loss of smell and difficulty breathing.

While some of these people eventually return to full health, a substantial number have symptoms for months with no clear sign that they will recover to how they were before infection.

Professor Danny Altmann, who has been one of the leading researchers studying long COVID, said he was very worried that the seriousness of this issue had not been fully understood.

“The bottom line is that we’ve acquired a very large group of very desperate, chronically unwell people and we don’t know if they’re going to be in that state for one year or two years or five years or 10 years,” he said.

“That’s an incredible new piece of our NHS healthcare jigsaw which you can’t solve by just trying a bit harder. The implications in terms of numbers of clinics, numbers of nurses, numbers of doctors, numbers of radiologists, numbers of therapists... it just goes on and on and on...”

The concern raised by Professor Altmann is that the impact of long COVID on the NHS could be on a similar scale to Chikungunya in South America. The lasting impacts of this viral disease – caused by a mosquito-transmitted virus that can result in debilitating long-term joint pain - have harmed health services in Brazil, by taking a substantial number of people out of work and putting them in chronic need of long-term healthcare.

“You can’t build that infrastructure overnight without investment and training, so the challenge is stupendous and the potential to destroy our healthcare system if we don’t get it right is absolutely enormous. I can’t really emphasise it sufficiently,” Professor Altmann added.

Professor Altmann spoke about the challenges with researching long COVID for Imperial's AHSC COVID-19 Seminar Series in November 2021

When asked about the possibility of treating long COVID, Professor Anthony Gordon acknowledged that it would take longer to work out how to treat persistent symptoms from the virus as more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of COVID and other viruses.

“It will inevitably take longer to work out how to treat these things, because if you are looking for what is the effect over one or two years, you have to wait those one or two years to try different treatments that may help,” he explained.

When we can save people's lives, it is important to ensure that patients survive and recover well.

While some symptoms of long COVID, such as chronic fatigue, have been seen with other viruses, it is still unclear why some patients face long-term illness and others do not.

Professor Gordon, who also works as a Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine at St Mary's Hospital in northwest London, said he hoped that awareness of long COVID would encourage more research into improving recovery from serious injury and illness.

“Many of the patients who become critically ill in the intensive care unit where I work are faced with months and years of recovery,” he said.

“I think it hasn't always been the priority area of research, because people naturally focus on saving lives. But when we can save people's lives, it is important to ensure that patients survive and recover well.”

Complex immunology

The other issue that has complicated our response to COVID-19 over the past year is the increasingly complex range of immunological responses to the virus around the world, creating a patchwork of protection.

In January 2020, the situation was relatively simple – you had a planet of people in which the vast majority had never seen the virus before, although some had seen similar ones in the form of common cold viruses or SARS viruses.

Now, we have a world with a diverse range of experiences with COVID-19. Some have first been infected with the original strain of the virus, others with the Alpha variant, Beta, Gamma, Delta or Omicron. Then others may have never been infected but have developed protection from one or two or three doses of different vaccines.

Those experiences will likely have an impact on our immune response to future variants of COVID, but it will take time to fully understand what the implications of those combinations are in terms of protection.

“If you take all that variability into account and say to me, would I bet my house on which is the universally best vaccine or approach to go for next? It’s non-trivial and it will take a tonne of research to work out,” Professor Danny Altmann said on the issue.

It is quite possible that in the short to mid-term, we get the establishment of antigenically distinct lineages [of COVID], which will co-circulate.

This diverse range of immunological responses to the virus is also likely to inform how the virus evolves over time, with the possibility that different lineages of COVID may co-circulate in different parts of the world.

Professor Wendy Barclay explained that Delta and Omicron, the two most prominent variants of the past year, have significant antigenic differences which mean a vaccine based on one will not necessarily provide the best protection for the other.

Not only that but the previous immune experience of an individual might shape how they respond to future variants or vaccines based on them.

“If you think of South America [where many people saw the Gamma variant first], they have been set up with quite a different immune history than South Africa, which had Beta first, or the UK, which largely had either vaccine or Alpha first,” she said.

“There are all kinds of different immune histories going on around the world and, therefore, different variants may emerge that do better or worse in those different immune populations.

“It is quite possible that in the short to mid-term, we see the establishment of antigenically distinct lineages, which will co-circulate.”

This problem is why some scientists are concerned about the idea of producing vaccine boosters specifically for Omicron, as it may produce a suboptimal response to a Delta-like variant that could emerge.

Imperial researchers, led by Professor Robin Shattock, worked on developing a COVID-19 vaccine

Imperial researchers, led by Professor Robin Shattock, worked on developing a COVID-19 vaccine

The ultimate solution to this would be to create a universal vaccine that works against all variants, but Professor Barclay cautioned that it is not clear how we would do this successfully.

A more achievable solution in the short to medium term, she said, would be to follow the lead of influenza vaccines, which include the four strains of flu that tend to circulate in one jab.

“A way to de-risk all of this is to have a multivalent vaccine where you have Omicron- and Delta-like components, because they sit on the extremes of the antigenic map and in that way, you cover all the antigenic space in the middle,” Professor Barclay said.

“With flu, we use a quadrivalent vaccine, so I think two or three SARS-CoV-2 strains within the same vaccine is very doable.”

Different variants have swept through different countries over the past year

In March 2021, the United Kingdom, Brazil and South Africa were facing three distinct variants of COVID-19 - Alpha, Gamma and Beta.

By August, the Delta variant had become dominant in the UK and South Africa, while its prominence was growing in Brazil.

By January 2022, all three countries had Omicron as their dominant variant.

The next pandemic

For most people, the end of the crisis phase of COVID presents an opportunity to relax and think about other priorities – but for many scientists, our experience with this pandemic shows why we need to strengthen our defences for the next disease threat.

While arguments rage in the UK around whether we followed the best strategy to manage COVID, it is clear that the country was poorly prepared to deal with a major outbreak.

When we asked Professor Peter Openshaw [first picture] about what the last two years had taught us, he noted that COVID-19 had shown the huge societal and economic damage that pandemics can cause and the need to have appropriate stockpiles of things like personal protective equipment (PPE).

It has also shown the need to act immediately to bring outbreaks under control once it becomes clear that a virus could cause major damage.

“For every few hours that you wait, you are seeing an exponential growth in cases, and it is very hard to bring outbreaks under control once they have been allowed to run,” Professor Openshaw said.

“Decisions have to be made in hours, not days or weeks.”

That view was echoed by Professor Katharina Hauck [second picture], an expert in health economics who is the Deputy Director of Imperial’s Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics.

While there is a trade-off between reducing cases and protecting the economy, at least in the short term, Professor Hauck found that this trade-off was often less severe for countries that introduced strict measures early to prevent widespread transmission.

“For example, for countries with stringent early mitigation, both deaths or infections and economic losses are lower” she explained.

“We are not talking about so many deaths, and we are not talking about the GDP losses that countries with slower reaction time had, such as the UK.

“Imagine that countries move on different curves trading-off deaths and GDP loss; once countries are on a high death/high GDP loss curve, it is very difficult to go back to a low deaths/low GDP loss curve.”

One thing we could do now to prepare for the next pandemic is make sure that we have the infrastructure in place to produce vaccines quickly in multiple countries so vaccine production can be more evenly distributed, according to Professor Wendy Barclay [third picture].

“It worries me still that the UK does not really have an onshore mRNA vaccine manufacturing capability,” she said.

“From a UK perspective, I do not really want to be dependent on a vaccine being manufactured somewhere else in the world, and low and middle-income countries in particular need help to make sure they can make vaccines, so they are not at the bottom of the waiting list.”

Another key measure Professor Barclay raised was a need to ensure we can rapidly scale up state of the art diagnostics to help control the spread of the virus at the earliest point.

This could be through surveillance studies like the REACT programme, which tests tens of thousands of randomly-selected people in England each month to give an understanding of the overall infection levels in the wider population.

Our relationship with animals

As well as thinking about how to prevent transmission when a new virus emerges, we should also think about where viruses come from, so we can potentially stop the next pandemic before it happens.

It remains unclear how exactly COVID-19 came to first infect humans, but Professor Charles Bangham, the Co-Director of Imperial’s Institute of Infection, warned that our contact with animals is the most common source of new viruses entering the human population.

“There are plenty more viruses to choose from [after COVID] and nearly all the emerging viruses come from a different or increased level of contact between humans and animals,” Professor Bangham explained.

Flu pandemics tend to come from birds or pigs, while coronaviruses like SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19) come from our contact with camels, bats and other mammals.

For Professor Bangham, one of the key measures that we could take is to minimise “ecological disturbances”, such as deforestation, that displace wild animals and lead to increased contact with humans.

Nearly all the emerging viruses come from a different or increased level of contact between humans and animals.

Meanwhile, Professor Wendy Barclay noted that we should also be aware of the risk posed by our relationships with domesticated animals that we farm and eat.

“I think identifying the high-risk activities of a populated world and trying to educate people around where the risks come from is one way that we can reduce the number of zoonotic incursions [diseases that jump from animals to humans],” she said.

“But I think we need to face up to the fact that even with the best will in the world, we're not going to capture every one of those and there will be further pandemics.”

A daunting challenge

There is hope though that COVID-19 has changed attitudes within governments about the threat posed by infectious diseases and the need to prepare for pandemic events, even if they require a large investment upfront to prevent another major outbreak.

“The message [about the risk of a pandemic] did not get through to policymakers with sufficient force and urgency,” Professor Charles Bangham said, when asked about the years that preceded COVID-19.

“The attitude was that these events are uncommon, most epidemics are not that severe, most of them are nothing like as bad as 1918-1920 pandemic, so it did not warrant the kind of investment that was needed.

“I think that the coronavirus pandemic, to some extent, is changing that attitude.”

We thought we were the bee’s knees in terms of pandemic preparation and look where that has got us.

Others are more pessimistic in their outlook. Professor Danny Altmann sat on some of the international pandemic preparedness groups in the 2010s, when the threat of a pandemic was an abstract concept for most people.

His fear is that the world is still in a similar place to where we were before 2020, with decision-makers failing to take the risk seriously enough to invest the level of money that is needed to prevent another disaster.

“I feel a bit daunted by it. We thought we were the bee’s knees in terms of pandemic preparation and look where that has got us,” Professor Altmann said.

“We weren’t as smart as we thought we were, and I’ve got no reason to think we’ve got any smarter in the meantime.”